Placing Stephanie Meyer’s “Eclipse” down on the table, I announced to my parents that I plan to attend Harvard when the time came. Although I had only been in the United States for some four years at that point, but I had come to understand that “smart” people in this country go to Harvard and I fancied myself a “smart” child. That’s an incredible amount of confidence for a child just shy of eleven to possess but it was a confidence that was built on top of the love and emotionally support I received as a child. Growing up, my mother would often tell me, “you can do anything, just work for it” and my father always nodded in agreement. Though it was true that my mother was a master at words of affirmation, she was also an incredible role model. An immigrant as well, my mother’s educational journey saw her beginning with English-As-A-Second-Language courses at community college in the mid 2000s to completing her PhD at the end of 2019. In this way, my mother had been in school in the United States for as long as I had been.

What I find curious about myself and my college peers is that we knew, one way or another, that we wanted to attend Harvard. I am uncertain where the vision of attending Harvard first originated as I lacked parents who attended Ivies and did not grow up in a neighborhood where Ivy League educations were the norm—something most, if not some of my peers at Harvard had. However, what is certain to me is that having parents who love you, support you emotionally, and are your most ardent supporters is a privilege. I’d argue that it’s as much of a privilege as having wealthy parents or being born in a wealthy country—something some, if not most of my peers at Harvard had.

Growing up with emotionally-supportive parents meant that I had internalized a winner’s mindset. After all, my mother’s favorite thing to tell me was, “you can do anything, just work for it.” So, I worked and was usually rewarded for my efforts. Well, that was until I arrived at high school. From the beginning, I believed I wasn’t where I should be. I had been rejected from Lakewood High School’s famed International Baccalaureate program (an offering that counselors in my middle school raved about to outgoing eight-graders) and I was attending a high school that was situated in a community that, although I had grown up in, I hadn’t fully been immersed in. Meaning, all the friends I had made in elementary and middle schools—the ones who had known me from the time I couldn’t speak English—were “down the hill” (the Coloradoan term for the area down the mountain in the foothills of Denver or in Denver’s metro area). So, I entered high school with no friends. However, I quickly made friends and it was a random conversation with a friend that led me to a club meeting that would forever change my life. In short, my friend took me to her meeting at Conifer High School’s Key Club and once there, I was intrigued by the club’s ideals of service to community and stuck around long enough to become Lieutenant Governor of the Rocky Mountain District (covering Colorado, Wyoming and parts of New Mexico) to later becoming International Trustee (where I served the Capital, Montana, Michigan, Ohio, Minnesota-Dakotas, Missouri-Arkansas Districts). For a high schooler, it was a big job: I frequently traveled to the states of my districts, attend District Board meetings while there and made myself as useful as possible within the context of my position by making myself available to answer questions, help settle board drama and wear the Crab Mascot for District events should it come to that (and it often did!).

I loved it. I loved it so much that I dedicate hours and hours of my time to it (eventually giving up both Volleyball and Tennis to total focus on being the best International Trustee I could be). So, when the time came for the election of Key Club International President (the position that oversees the board that oversees a 60,000+ strong high school service organization), I lost, and I lost spectacularly. But it was losing this election—the one I had spent all my high school years working towards—that showed me that God has a sense of humor.

What I’ve come to appreciate about my mother’s parenting, and my father was like this as well, is that she doesn’t allow me to sulk. When I called her to explain that I did not obtain the one goal I had been working the past three years towards, she told me, “cry for a day then get over it.” After my twenty-four hours had passed, I began writing the essay that would seal my collegiate fate. Because I had spent the better part of my childhood with a winner’s mindset, I had envisioned my high school self writing a college essay that was sure to be a tale of triumph, a victor recounting an epic spoil. So, it was heartbreaking to write an essay that was truly a musing from the losing side. What’s ironic, is that it’s precisely that I told Harvard I lost that I gained admissions. At least, this is my theory. When I read my college essay, I don’t see a tale of failure. I see a high schooler who had never lost anything meaningful in her academic or extracurricular life learning for the first time that effort does not equal outcome. An incredible lesson for an 18-year-old to know. With this lesson learned, I made my way to Cambridge, Massachusetts to begin the next phase of my life.

“Cry for a day then get over it.”

My mother’s rule of thumb is to never spend more than 24 hours crying or complaining about something. Onward and forward is the Noelle Dilgarde way.

Before I stepped foot on Harvard’s campus as a student (my greatest childhood wish), my mother took me and my father back home with her. Although my mother and I had been both been born in Douala, Cameroon, it was her who had been raised there; my father was a white man of Germanic descent who had been raised in Wyoming and Colorado and met my mother when she was in Chicago. Needless to say, it was a transformative trip for everyone. For me, this trip left me with a clear path forward. As I saw the boundless opportunities that existed within Cameroon (everywhere I went I saw construction and I heard countless stories of diasporic entrepreneurs who had set up shops, businesses, and opened hotels and apartment buildings—effectively giving a developing country a robust, if not small, means of economic opportunity for its citizenry) and knew that I had to make my way back to the African side of the Atlantic. So, I went to Harvard determined to learn everything I needed to know to be an African entrepreneur. I joined Harvard Undergraduate Women in Business (the largest undergraduate group on campus), Harvard College Consulting Group (the premier consulting group on campus) and even briefly flirted with Harvard Financial Analysts Club. Although I ultimately settled on studying Romance Languages & Literatures as opposed to the far more popular Economics and surreptitiously ended up pursuing a secondary in African Studies (I was made aware I had satisfied the minor requirement my senior year), I kept my extracurriculars strictly business. Literature, the arts, humanities, these were all interests given to me by my artist father and if there was ever a place to study them, I felt Harvard was it.

Outside of the academics, I found Harvard to be a place of extremes. Even the most average person among the student body is an outlier anywhere else. The one extreme I would always see is how easily, effortlessly, and leisurely people spoke of privilege—not so much the analyzing of it, but the obtaining of it. Cameroon isn’t the richest country on the planet but there are Cameroonians who are well off within the context of the country so I understood privilege going into Harvard. What Harvard would later teach me is this thing called access. I’ll never forget when a preceptor said that “what this place [Harvard] teaches you is how to interact with elites” or when my Economics 10 (the famed freshman introductory Economics course that almost, or so it seems, every freshman at Harvard enrolls in) Teaching Fellow, when speaking of the American Gini Coefficient chart on the screen, “all of you [the students present for his review session] have the ability to enter the top 10% if you choose.” To me, these were absurd things to hear but certainly say—at least out loud. Consider what it means to have the ability to choose to enter the top 10% in a country with rising income inequality. Consider what it means for the by-product of an institution’s culture is comfortability around elites (there’s an interesting question here on how one defines elites, but that’s a question for perhaps another musing). What these considerations left me with was the fundamental understanding that what Harvard College teaches its students is to have confidence in themselves. At its best, Harvard produces people who feel they can do anything. At its worst, Harvard produces people who feel they can do anything.

“At its best, Harvard produces people who feel they can do anything. At its worst, Harvard produces people who feel they can do anything.”

Audrey Dilgarde, My Harvard Experience and The Necessity of Perspective

In January of this year, I spent Christmas and New Years with my family in Cameroon. It was a much needed holiday as many things had shifted in my life since I had been in the country back in 2018. My father had passed away at the beginning of my junior year, I had endured college amidst a pandemic that was still raging but on the bright side I had secured a job post-graduation. Catching up with my family, one of my cousins, Steve (who is set to be one of the foremost filmmakers on the African continent though I admit I am bias) spoke to me of his friend. Steve told me his friend is the poorest person he personally knows yet is the happiest person he knows. Reflecting, Steve said, “il pourrait vivre ma vie, mais je ne pourrais vivre la sienne.” To my English readers, Steve told me that his friend could live his life—Steve’s—but that Steve could not live the life of that of his friend. Effectively, Steve was telling me that life is about perspective and that without it, we are unable to see the blessings inherent in life as we tend to get fixated on what we lack, unable to focus on what we have.

This question of perspective followed me as I returned to the States to finish my final semester at Harvard. So, when the opportunity came to participate in the oldest tradition at Harvard and deliver a homily at Memorial Church during Morning Chapel, I ran to church with an eagerness that would have made my very Christian, African mother proud. For background, the story goes that back when the College was an institution principally concerned with educating Theologians, attending chapel every morning was mandatory. This practice endured well into the late 19th century when Harvard ended required chapel in the 1880s. In the years since, every spring, one senior is selected from every House to deliver a homily at Memorial Church beginning at 8:15am—what back in day would have been chapel. On the 20th of April in the year of our Lord 2022, I felt I had something to say so I walked into Memorial Church with words I hoped would touch at least one person in the sanctuary:

Inspired Text

James 1 (New International Version [Anglicized])

1James, a servant of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ,

To the twelve tribes scattered among the nations:

Greetings.

2Consider it pure joy, my brothers and sisters, a whenever you face trials of many kinds, 3because you know that the testing of your faith produces perseverance. 4Let perseverance finish its work so that you may be mature and complete, not lacking anything. 5If any of you lacks wisdom, you should ask God, who gives generously to all without finding fault, and it will be given to you. 6But when you ask, you must believe and not doubt, because the one who doubts is like a wave of the sea, blown and tossed by the wind.

Address

During my Undergraduate years, there’s been many waves. There were moments when the waters were still, things were calm, and life was good. And then, the water would rise and its level ever-increasing until I was engulfed in disillusionment and the persistent feeling that more could have been done and the lingering belief that things just weren’t going my way.

But as the water subsided and the waves retreated, I was left dazed but not so confused for I had come to the realization—as one often does after Hard Times—that I had not been fearful that negative outcomes would occur but then I had been faithful that negative outcomes were inevitable as fear is merely faith in evil rather than faith in good.

You see, when you are going through consistent Ups and Downs; when you are working through long nights and early mornings, it is easy to orient your faith in disillusionment—in disbelief. But when I realized that my problems were the result of perspective rather than circumstance, the waters stilled, and the waves were no more.

This shift in perspective became the bedrock of my patience for I now understood that God denies to give. It’s this knowing—this confidence in a divine conspiracy of circumstance—that has allowed me to walk by faith, and not by sight.

So, as those waves ebb and flow, whatever cycle they may be, let us remain patient and utilize this patience as the wellspring for our faith: in good, not in evil—for nothing is inevitable unless we deem it so.

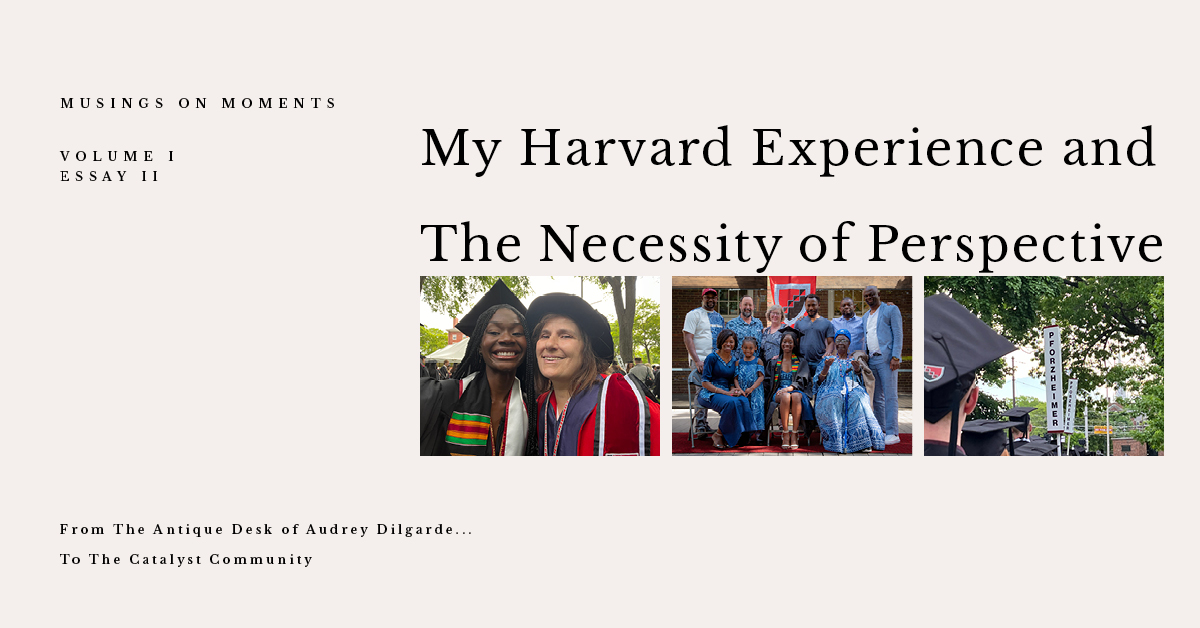

When I reflect on my biggest takeaway from my time at Harvard, I am left with the belief of the necessity of perspective. In Cameroon, it was my cousin Steve who really got me to see the importance of perspective but it was at Commencement where I understood its necessity. Towards the end of the graduation ceremony, the Pusey Minister of Memorial Church gave a Benediction and said, “blessing is a way of seeing.” In that moment, it became clear to me that what Harvard gives its graduates is not (just) confidence, but a way of seeing. Indeed, what Harvard gave me was perspective. With its pomp and its circumstance, with its urging of righteous love and remainders of responsibility, the Harvard College Commencement for the Class of 2022 was a beautiful goodbye to the institution that gave me perspective, a way of seeing; with its good and bad, Harvard was everything a little girl from Douala, Cameroon had envisioned for herself and more.

Thank you so much, Changemaker, for reading till the very end.

Until next time,

Audrey Dilgarde

such a stunningly honest and poignant message. thank you sharing and congratulations on your alumna status!!

Thank you Kristian! I much appreciate your kind words!!

What a lovely moving story. You’re quite the art! Congratulations on your commencement graduation and Hood luck to your future.

Thank you Lisa! Your kind words are much appreicated